The Village Smithy

October 16, 2014

Although many have forgotten much of the history they learned at school, most can probably remember at least that the Stone and Bronze Ages were followed by the Iron Age, which dawned about 4,000 years ago and was to significantly shape the course of history.

Before it’s discovery, other available metals, such as tin, coppper, silver and gold were malleable and could be worked cold, but were not very strong. It was then found that iron, heated at high temperature, shaped whilst hot and cooled rapidly was immensely hard and durable. It also turned out to be the fourth most plentiful element in the earth’s crust – both accessible and widespread. Iron is extracted from four main ores, of which magnetite, a black oxide, is most commonly used. This became known as ‘black metal’ from which the term ‘blacksmith’ arose.

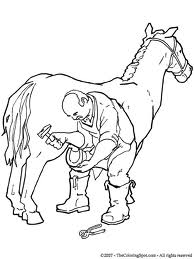

The earliest smiths were itinerant, travelling from manor to manor to fashion armour and weapons for their squires, who were always off to war somewhere or other. Some found permanent work in the castles of the nobility, where the need for security was met by the forging of grilles, stout hinges and locks – today’s wrought iron gates are a direct descendent of the portcullis. In time their work expanded to serve the needs of a largely agricultural society, and the first workshops appeared in most villages – usually sited strategically in the centre of a village at a crossroads. Soon, no rural community could exist without it’s smithy, it was the hub and very heart of the village. Here, horses were shod, craftmen’s tools, farm implement and domestic necessities were manufactured and mended. It was also a popular place to get warm and exchange gossip.

The blacksmith had , first and foremost, to be a strong man, and very much his own master. He was highly respected and, in the Middle Ages was believed to have supernatural powers, which included horse-whispering. He was often called on for advice or to arbitrate in village disputes and, as a sideline, sometimes acted as village barber or tooth-puller! He was even permitted to carry out a form of wedding ceremony over his anvil.

The design of the cast iron changed little over the centuries, with its square ‘face’ at one end and the conical ‘bick’ at the other, on which horseshoes, loops and links were shaped. It was mounted on a stout wooden block, usually elm, that acted as a shock-absorber and provided ‘bounce’ for the hammer. Hammers and tongs, virtual extensions of the Smith’s hands, were his most important tools and hung with a variety of others beside the forge or furnace. In front was the ‘bosh’, a water trough in which the hot iron was quenched. The blacksmith’s leather apron was often fringed at the hem to brush dross off the anvil. He could not work entirely alone; he needed a labourer or an apprentice to hold the horses and carry out simple tasks. Under the Smith’s instructions, he would work the 6 foot wide leather bellows, which delivered a forced draught into the furnace through an iron ‘truyere’ or nozzle. Juding the required heat was a particular skill; the various colours of the heated metal were given nicknames that ranged from ‘slippery’ through several shades of red to ‘snowball’ white and the hottest of all.

The Industrial Revolution led to the inevitable demise of the Smithy. Farriery, however, remained much in demand and went on to develop into the specialised profession we know today.

JR